Do You Suck At Sequencing Drums? Let's Fix That!

One of the most common questions we get when working with new producers or musicians looking to get into production is how to start sequencing drums from samples and VST instruments.

Why would a person who plays an instrument already (even a drummer!) have the same problems as a totally green producer? The instrument is already doing a lot of heavy lifting to create that sound when you play a single note on a real drum.

When a great drummer plays even a simple beat, there is a lot more complexity going on under the surface that one might think. When you are working on a hardware sampler or computer you have to tell the machine one step at a time to do all the things real drums and real drummers do without much extra effort.

This article gets into the little subtleties that you need to program great drum loops in electronic music genres like house music, hip hop, and drum n bass, using sample packs or your own home brewed sounds

What is Drum Programming or Sequencing?

Sometimes people hear the word "programming" and think you're writing computer code. You can of course, but most of the time drum programming or sequencing drums means telling a sampler when to play back drum sounds with MIDI or using a hardware sequencer's internal software to decide when to trigger notes.

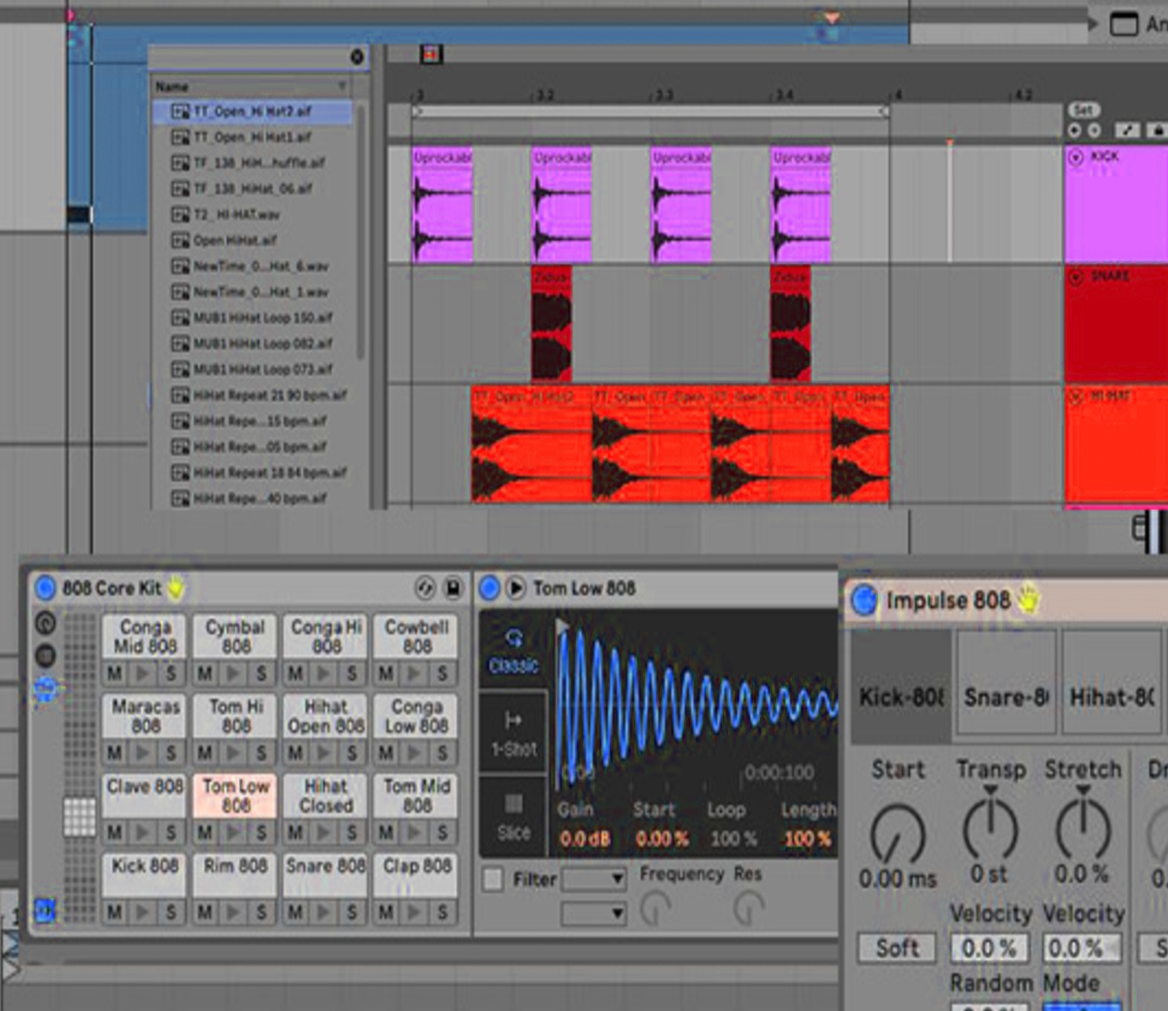

A lot of music production commonly involves placing notes on a MIDI piano roll in a DAW like Ableton, Logic, or Pro Tools.

How do the notes get there? You can record a performance using controllers or triggers, a producer can click on the piano roll where they want notes to occur, or you can use devices like arpeggiators to generate parts.

You can do this with any sound you want too. Can be a virtual instrument, free samples you found somewhere, special effects, literally anything. You can use normal drum sounds, or you can use really different samples to compose the rhythmic foundation of your tracks.

So don't be intimidated by drum programming. At its simplest it is just inputing a drum pattern. But that's where it starts. There is a lot of detail and subtly that goes into it as you become more advanced.

MIDI vs. Audio

There are basically two ways that a musician might go about sequencing drums:

- Programming a note which tells a sampler or plugin to play a note.

- Or you can just drag and drop audio samples from your device directly into the timeline of a DAW and not worry about using MIDI notes at all to create drum patterns.

These two methods have their pros as well as their cons. Most beatmakers and producers use a mix of both and have their personal preferences when sequencing drums. MIDI is more flexible and can be manipulated in interesting ways, but we find using raw audio is faster.

Audio Player Madness

You can literally just start dragging stuff into the timeline and nudging it around until things sound right. Find a sample pack you like and start making drum beats right in the timeline! You can always flatten it to a single wave file later to make it easier to work with, or drag that new file into a sample and trigger it with MIDI as you would a drum break.

Drum Programming Basics

In genres like EDM, rock music, or hip hop the sounds used are typically rooted in what is available in a regular drum kit, like a kick drum, snare, hi hats, cymbals, and toms.

But!

In modern music, your percussion sounds can be whatever you want. There are literally no limits other than what your computer can keep up with.

Want to bang two sticks together and turn that into your closed hi hat sound? People do that kind of thing all the time. Also, it's pretty common to used sampled drum machine sounds that are interesting, but don't actually sound much like real drums. For example, a snare drum sample might just be gated noise.

The most important thing is to just keep an open mind about what a drum sample can be when sequencing drums.

Creatively, we find it helps to impose some limits on yourself. Having every available option at all times is usually more overwhelming than inspiring. Find a sample pack and make yourself figure out drum patterns using only that. Or limit yourself to a specific drum machine and see what you can make.

I know the basics, but how do I get better at drum programming?!

If your drums sound boring, bad, out of time, or you are stuck doing the same thing over and over again we have good news.

99% of the time it means you have one (or several) of the following problems when sequencing drums:

-

You don't know basic drum patterns or how to learn new ones from songs you like.

-

You don't understand syncopation, cross rhythms, meter or other basic structures.

-

You're trying to work with drum samples that suck or don't fit the genre.

-

You're trying to program everything "on the grid". If you nudge things off the grid, like the tutorials say, it sounds worse :(

-

You don't have an understanding of how real, human drummers actually play.

-

You're on the right track, but you don't know the basics of a drum good mix.

-

You see YouTubers or friends process a bad sound into just the right sound, but you can't do this yourself.

We're going to go through these one by one to help you be on your way to successful drum programming.

Don't try to learn everything at once

You need to focus on one component of drum programming at a time. If you try to learn everything at the same time, most people get overwhelmed and give up.

Don't chase two rabbits at the same time, that's a great way to make sure you catch neither. Pick one thing and focus on that for a while.

For example if drum patterns feel murky and confusing, spend a month of two just studying different patterns. A real drum set player spends a lifetime on this.

It might feel like you're not doing much at first, but once you've done the work, you have the knowledge forever and it stacks up over time. So dive in and trust the process!

Let's dive in and explore how to deepen your drum programming knowledge.

Problem #1: You don't know basic drum patterns or how to learn new ones from songs you like.

Lots of people will search around for "cheat sheets" of drum patterns stick to repeating 2-3 patterns they know.

We think it's a lot more important to understand why certain elements of a drum pattern are there to begin with and learn lots of grooves from different tracks that inspire you. Then, when you go about sequencing drums you will have a lot more creative freedom.

Instead of digging around on Google for a quick hack, we think it's really worth the time to study the music you're into and pick it apart.

Amen Brother

To start learning basic drum patterns pick a song you want to analyze. Start with the "amen break" by The Winstons if you have no idea what to pick. Its deceptively simple and serves as the rhythmic backbone to lots of music, so it's worth picking apart.

First you want to listen for how many drum elements you hear. Is there a kick drum? A snare? Hi hat? Some weird blip that's being used as percussion? Maybe there's two snares, a high pitched snare drum and a low pitched one.

Next, dub a few measure of the song into your DAW and arrange it so the beat is in sync with the project tempo (being able to turn the metronome on and off is helpful).

Now you're going to try to recreate the beat in a MIDI track below that with any sounds you have. Program a kick drum where the kick hits, the hi hat on the same beats, etc until you have every element covered.

Let it suck!

It's fine if your recreation of the beat sounds kind of simple at this point. It might not, sometimes it sounds pretty cool right away.

But if it sucks, let it suck! You're not trying to compose a finished beat, you're doing this to analyze the pattern. What beats do the snare and kick hit on? Do you notice any patterns that come up?

If you get yourself into the habit of doing this often, you'll start to intuitively "know" where things should go without thinking about it too much.

Doing this with 10-20 beats is a good start, but ideally this will become how you pick apart a new beat you don't fully understand. After a few dozen boom-bap hiphop beats you'll have a pretty good idea of how drum patterns work in that genre, but when you run into some crazy 5/4 trap drum pattern you've never heard before, you now how a system to pick it apart and understand what's happening.

Problem #2: You don't understand syncopation, cross rhythms, meter or other basic structures.

Basics of Meter

If you don't understand what 4/4 time means vs 5/4 or 3/4, what triplets are, or how to beat up a beat into smaller units, looking at the grid in your DAW will be confusing and you're not going to be able to reproduce more complex rhythms.

Let's understand the basics of that right now.

4/4 time means you have 4 beats inside a measure of music. A measure of 5/4 would mean there are 5 beats inside a measure (not as common, most commercial Western music is in 4/4)

The pattern starts on beat 1. Think of a measure as just a unit of time. You can string together a bunch of them to make more complex things later, but lets keep it simple.

In electronic dance music or techno, you might put a kick drum on every beat. Your DAW metronome clicks on every beat. These are sometimes referred to as a quarter note because they take up one quarter of a measure in 4/4.

You then can break up each beat into smaller beat. If you play 2 notes on every beat, you can make the basics of a simple hi hat pattern. These are called 1/8th notes. Each note is one eighth of a bar. Noticing a pattern?

But what if you played 3 notes per beat? Those are called triplets. What about a 16th note? Totally fair game. They're twice as fast as 1/8th notes so they mix will together.

These are just the basics. If you understand this, you have a decent framework for analyzing new rhythms that aren't yet in your vocabulary.

Cross Rhythms & Syncopation

Programming too many notes of the drum beat on strong beats (directly on beat 1, 2, 3, 4 in 4/4 time) sounds square and boring a lot of the time. The notes that make things groove and make you want to move are the things between beats. Or the notes that sometimes land on the beat.

If you want a good example of a basic cross rhythm, try this.

In 4/4 time, make a few measures of music with the kick playing only on strong beats. There should be 4 in every measure. Now with a hihat or other short sound, program a new note every three 16th notes. The way it works out it will sometimes line up with the beat, but mostly won't.

However the two elements co-exist and things start to groove more. Generally, interesting beats are going to have little piece of these kinds of cross rhythms that make you anticipate strong beats, or feel two patterns at once. This is what makes things groove unlike straight quarter notes.

Problem #3: You're trying to work with drum samples that suck or don't fit the genre.

This is obviously very subjective! What fits and what doesn't? A lot of that is beholden to the creativity of the producer. But generally speaking, if you're trying to make lofi hip hop with a sample pack of big room EDM risers, you're going to have to be really heavy handed to get those sounds to work in that genre.

Another common problem is trying to force samples that just aren't good. Yes you can do things like manipulate "found sounds" into almost any musical element, but if you have a snare with a resonance that clashes with the key of the song or an 808 that doesn't have enough bass, you're fighting an uphill battle.

Digging for samples is part of the production process so we encourage you to do it often. Get an extra hard drive and make that where you stash you sample library. That way, when you're working on a drum part and a sound just doesn't fit, no worries. Swap in some other individual sounds and move on instead of trying to force something that isn't meant to be.

Problem #4 & 5: You're trying to program everything "on the grid" and you don't understand how drummers actually play.

Nudging drums is an easy trick that sometimes makes quick a big difference, but remember that when you nudge a whole hi hat pattern for example, it's still "on the grid" you're just displacing everything a little. The relationships between the notes have not changed!

Instead you need to start experimenting with the "swing" of the beat. Proficient drummers all have a swing to the way they play, meaning they don't play on the grid, ever. If they play 16th notes, some of them will be a little ahead or behind where the grid lines sit in your DAW and they'll never be exactly the same twice.

This is defined by subtle differences of timing and velocity that add to grooves and rhythmic nuances of loops. Software like Ableton or hardware like the MPC allow a producer to apply a swing (in Ableton its called the Groove Pool) to notes that help capture some of the variation the a real drummer would have when they play.

Study the real thing

If you really want to get in the weeds and look at the details, get a drum loop of a real drummer playing, sync it you your project BPM and look at how the individual drum beats line up with the grid in your DAW software.

Do the strong snare and kick beats hit exactly on the grid lines? Hell no. They'll be close, but generally a little ahead or behind and never exactly the same. There will probably be even more looseness with ghost notes and anticipatory notes. Some drummers play looser than others too.

These subtle variations are what give a drummer their specific sound and groove, so if you want to capture some of this when you start sequencing drums in your own programmed beats, we strongly recommend getting it from the source!

Problem #6: You're on the right track, but you don't know the basics of a drum good mix.

When programming drums, you don't need to have a perfect mix, but if elements aren't generally balanced it can change how you perceive the groove of the music you're writing.

A common mistake is having sustained, high frequency spectrum heavy elements too loud, like ride cymbals and open hi hats.

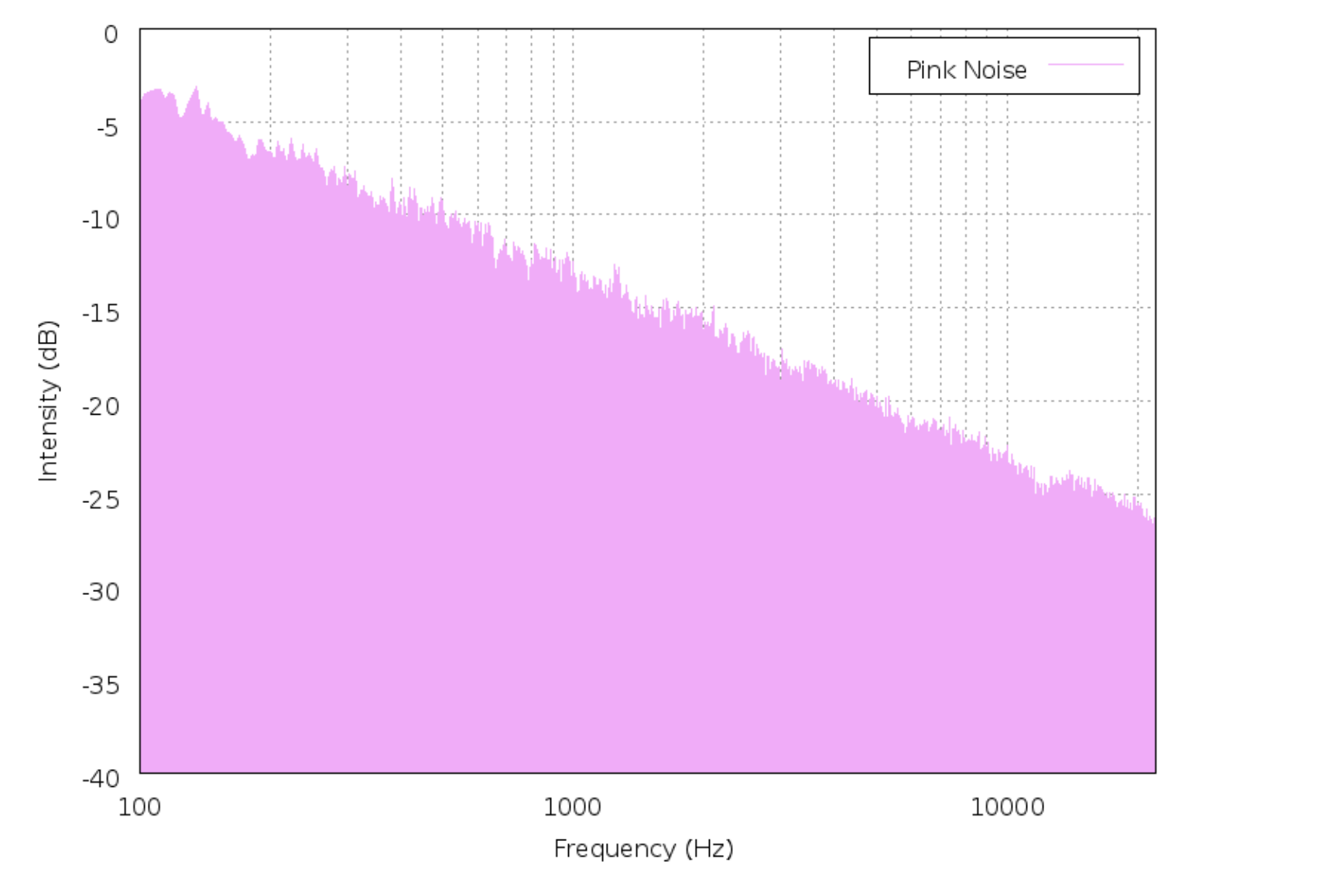

Utilize the Pink Noise Curve

A good starting place to balance the drum mix when you're still in the programming stage are to keep the bass drum and snare drum elements balanced with each other—one shouldn't be dramatically louder than the other—and make sure nothing is clipping unintentionally. Then slowly bring up the high frequency elements like hats, cymbals, and auxillary percussive elements.

To help train your ears to hear the right balance, turn on the pink noise curve if your meters have it, or just pull up an image of one online. The gentle slope in the high end of pink noise makes a good reference to make sure the elements that live up there don't get too loud, which is a common problem for many people when they are starting out.

Problem #7: You see YouTubers or friends process a bad sound into just the right sound, but you can't do this yourself.

YouTube is an absolute goldmine and there are many people making videos that get into the nuts and bolts of how music works, including us. This is great.

However, we've noticed that a lot of tutorials are kind of like cooking shows. They have certain things pre-made ahead of time and they had to fuss with their examples to behind the scenes a lot for the sake of making a concise, clear video.

Or if they do sound design on the fly, they know exactly what they're looking for and how to get there. This is not their first rodeo. That quick, on the fly example has thousands of hours of reps and practice behind it.

So of course if you're still learning basics of sound design like using ADSR envelopes, filter envelopes, stereoizing techniques, learning the common DSP effects, you're going to struggle sequencing drums even with pretty basic tools.

Unfortunately, there is no shortcut here. Sound design is a huuuuuge huge topic. You need to just dive in and start learning if you want to get better at this component.

Just don't worry if you feel overwhelmed. This is a GOOD thing. Yes, sound design can be explored for a lifetime, but this means there's an endless fountain of inspiration there. Anything you can master and know inside and out after a few years will get boring eventually because there is nothing new to discover. Sound design isn't like this. There is always a new thing to discover

Sequencing Drums - Wrapping it up

We know this is a complex topic and there are endless tutorials out there explaining parts of the process. We hope that this was able to help you structure some of that learning and give you an idea of what to learn first before moving on to other components.

Every topic has pretty much been covered somewhere when it comes to writing music and understanding rhythm so coming up with a plan of attack to digest all of it is essential.

Let us know how we did and and don't forget to check out some of our sounds and devices to juice up your productions.